Wood fibers are the backbone of the global paper industry. Whether producing tissue, printing paper, packaging board, or high-performance specialty grades, the quality of the final sheet heavily depends on the inherent properties of the fibers used. These microscopic structures determine strength, brightness, opacity, softness, drainage, formation, and dozens of papermaking characteristics.

In this article, we explore the core properties of papermaking wood fibers—from anatomical structure to chemical composition, bonding potential, and performance impacts.

What Are Wood Fibers?

Wood fibers are long, tubular, cellulose-based cells obtained from softwood or hardwood trees. During the pulping process (chemical, mechanical, or semi-chemical), these fibers separate and later form bonds when dried to create paper.

Wood Species Used in Papermaking

- Softwoods: Pine, spruce, fir, hemlock

- Hardwoods: Eucalyptus, poplar, birch, acacia

Each species provides unique fiber characteristics that influence paper grades.

Major Properties of Papermaking Wood Fibers

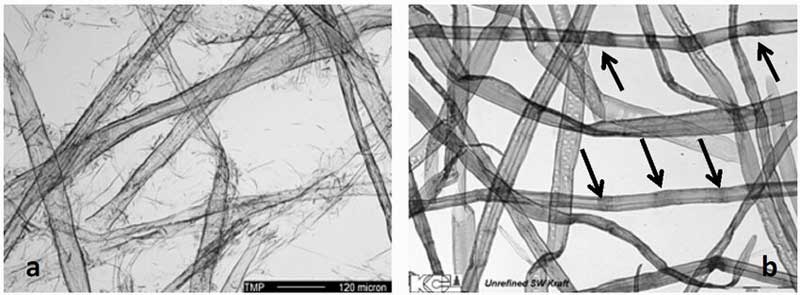

1. Fiber Length and Width

Fiber length is one of the most important morphological properties. The aspect ratio (length-to-width) determines how well fibers interlock. Longer fibers create more “bond sites,” leading to higher tensile strength. However, if fibers are too long, they may clump together (flocculation), causing an uneven look known as poor “formation.”

Softwood Fibers

- Average length: 2.5–4.5 mm

- Provide excellent tensile strength and tear resistance

Hardwood Fibers

- Average length: 0.7–1.5 mm

- Improve smoothness, formation, and printability

Why Length Matters

- Longer fibers interlock strongly → higher strength

- Shorter fibers pack densely → smoother surfaces

Modern papermaking often blends hardwood + softwood fibers to balance strength + surface quality.

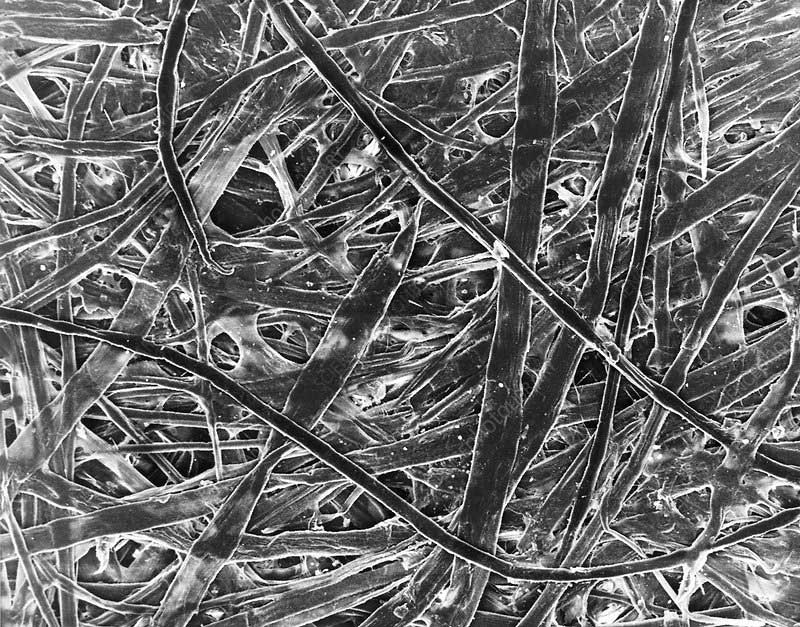

2. Fiber Cell Wall Structure

Wood fibers contain a layered cell wall composed of:

Layers

- Primary wall (P)

- Secondary wall (S1, S2, S3)

- Lumen (central hollow area)

Why Structure Matters

The thickness of the S2 layer and the size of the lumen determine:

- Flexibility

- Collapsibility

- Bonding potential

- Water absorption behavior

Softwood fibers have thicker walls, while hardwood fibers have larger lumens.

3. Chemical Composition of Wood Fibers

Wood fibers are primarily composed of:

| Component | Approximate Range | Importance |

| Cellulose | 40–50% | Provides strength and flexibility |

| Hemicellulose | 20–30% | Enhances bonding and water retention |

| Lignin | 18–30% | Gives rigidity; removed during chemical pulping |

| Extractives | 1–5% | Affect resin and pitch formation |

The performance of wood fiber is governed by three primary organic polymers: Cellulose, Hemicellulose, and Lignin.

Cellulose: The Backbone

Cellulose is the primary structural component. It consists of long-chain glucose molecules that provide the fiber with its inherent tensile strength. In papermaking, we aim to preserve as much cellulose as possible.

Hemicellulose: The Natural Adhesive

Hemicellulose acts as a biological “glue.” It is more chemically reactive than cellulose and helps in hydration during the pulping process. High hemicellulose content makes fibers swell more easily, which promotes better fiber-to-fiber bonding.

Lignin: The “Enemy” of White Paper

Lignin is the rigid resin that holds trees upright. However, in papermaking, lignin is often undesirable:

- Brittleness: It makes fibers stiff and difficult to bond.

- Discoloration: Lignin turns yellow when exposed to UV light (think of old newspapers).

- Removal: Chemical pulping (Kraft process) is designed to dissolve lignin while leaving cellulose intact.

Key Insight

Higher cellulose = stronger, more flexible fibers

Higher lignin = stiffer fibers (good for mechanical pulp, poor for bleaching)

4. Fiber Flexibility and Conformability

Fiber flexibility is the ability of fibers to bend and flatten.

Benefits of High Flexibility

- Higher fiber bonding

- Better sheet consolidation

- Higher tensile and burst strength

What Influences Flexibility

- Lignin content

- Fiber species

- Pulping method

- Refining intensity

Chemical pulping + refining → highest flexibility

5. Fiber Bonding Ability

Bonding ability determines paper strength and quality.

Bonding depends on:

- Fiber surface area

- Fiber swelling

- Fibrillation (fibrils raised by refining)

- Fiber collapse and flattening

- Cellulose exposure (after lignin removal)

Stronger bonding results in:

- Higher tensile strength

- Better burst

- Improved Z-direction strength

- Superior print surface

6. Fiber Coarseness

Coarseness is the dry mass of fiber per unit length.

- Softwood fibers = higher coarseness

- Hardwood fibers = lower coarseness

Impacts

- High coarseness → bulky, stiff paper (e.g., packaging)

- Low coarseness → smooth, dense paper (e.g., printing & writing paper)

7. Fiber Curl and Kink

Fiber curl is the deviation of a fiber from straightness.

Positive Effects

- Improves tear strength

- Enhances bulk

Negative Effects

- Reduces tensile strength

- Increases drainage time

- Reduces bonding

Refining reduces curl by straightening fibers and increasing fibrillation.

8. Fiber Fines Content

Fines are small particles generated during pulping and refining.

Good Fines (primary fines)

- Improve bonding

- Increase sheet density

Bad Fines (secondary fines)

- Reduces drainage

- Raises chemical demand

- Causing sheet picking during printing

Modern mills use screening and fractionation to adjust fine levels.

9. Fiber Swelling and Water Retention Value (WRV)

Fiber swelling increases the fiber surface area. It provides enhances bonding, stronger sheet and higher drainage resistance. WRV is a common test used in laboratories to measure the water a fiber can retain.

10. Surface Chemistry and Charge

Wood fibers naturally contain carboxyl groups that generate an anionic surface charge.

Why Charge Matters

- Affects chemical retention

- Controls interactions with starch, fillers, and retention aids

- Enhances adsorption of additives

Chemical pulping and bleaching increase fiber charge, improving bonding.

Softwood vs. Hardwood Fibers

Not all wood is created equal in the eyes of a paper chemist. The industry broadly categorizes raw materials into two camps, each offering distinct advantages.

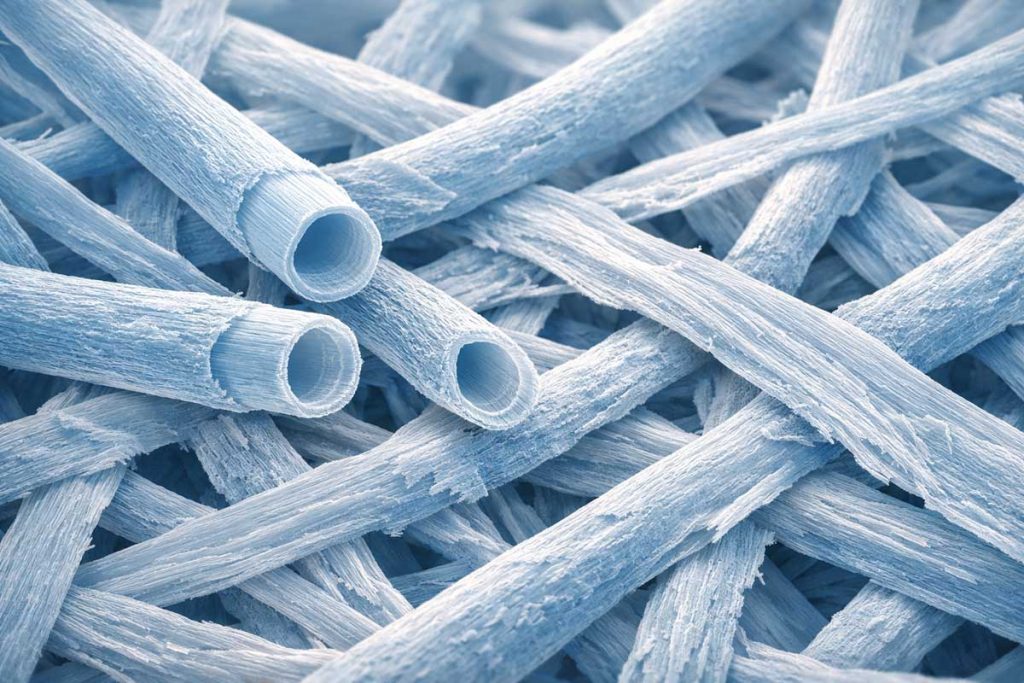

Softwood Fibers (Gymnosperms)

Softwoods, such as pine, spruce, and fir, are the “muscle” of the paper industry.

- Fiber Length: Typically 2.5–4.5 mm.

- Characteristics: Long, flexible, and strong.

- Primary Use: Provides structural integrity and tear resistance. Essential for packaging, grocery bags, and high-strength shipping containers.

Hardwood Fibers (Angiosperms)

Hardwoods, such as birch, eucalyptus, and aspen, provide the “skin” or finish.

- Fiber Length: Typically 0.7–1.5 mm.

- Characteristics: Short, stiff, and numerous.

- Primary Use: Improves opacity, smoothness, and printability. These fibers fill the gaps between longer softwood fibers, making them ideal for office paper and premium magazines.

Key Performance Properties

- Tensile and Tear Strength

Tensile strength (resistance to being pulled apart) is driven by the internal strength of the fibers and the quality of their bonds. Tear strength (resistance to a snag) is more dependent on fiber length. - Hygroscopicity (Moisture Response)

Wood fibers are hydrophilic—they love water. When humidity rises, fibers swell in width significantly more than in length. This is why paper curls or jams in a printer on a humid day. - Opacity and Brightness

Short hardwood fibers increase opacity because they create more surfaces for light to scatter. Brightness, meanwhile, depends on the efficiency of the bleaching process in removing residual lignin.

How Fiber Properties Impact Different Paper Grades

- Tissue Paper

- Needs soft, flexible hardwood fibers

- Short fibers improve softness and absorbency

- Printing & Writing Paper

- Smoothness: hardwood

- Strength: softwood

- Fillers: up to 30% to enhance brightness and opacity

- Packaging and Kraft Paper

- Long softwood fibers → high tear and tensile

- High lignin mechanical pulp for stiffness

- Specialty Papers

- Tailored blending

- High-purity cellulose for chemical resistance or electrical insulation

The Refining Process: Modifying Fiber Properties

In a mill, fibers are rarely used in their raw state. They undergo refining (beating).

Refining mechanically bruises the fibers, causing:

- External Fibrillation: Small “hairs” peel off the fiber surface, increasing the surface area for hydrogen bonding.

- Internal Fibrillation: The fiber becomes more flexible and “squishy,” allowing for better contact with neighbors.

- Fines Generation: Small fragments are broken off, which help fill the voids in the paper web.

Refining improves fiber properties by increasing fibrillation, enhancing bonding, reducing curl, and increasing surface area. But over-refining leads to reduces drainage, increases energy consumption, and produces excessive fines. A balanced refining strategy ensures optimal paper strength and runnability.

Conclusion

Papermaking wood fibers play a foundational role in determining the strength, quality, and performance of paper. Their morphology, chemistry, flexibility, bonding ability, and response to refining all influence how well a sheet forms and behaves. Understanding these fiber properties allows papermakers to choose the right pulping method, wood species, and refining level to achieve the perfect balance between strength, smoothness, bulk, softness, and print quality.

FAQ

1. What are the most important properties of papermaking wood fibers?

Fiber length, width, cell wall structure, chemical composition, flexibility, bonding ability, coarseness, and charge level are the most crucial properties.

2. Why are softwood fibers stronger than hardwood fibers?

Softwood fibers are longer and have thicker cell walls, resulting in higher tensile and tear strength.

3. How does refining affect wood fibers?

Refining increases fibrillation and flexibility, improving bonding and strength but can reduce drainage if overdone.

4. What is the role of lignin in papermaking?

Lignin adds rigidity to fibers and is removed during chemical pulping to improve bonding and brightness.

5. Why do paper mills blend hardwood and softwood pulps?

Blending balances strength (from softwood) and smoothness/formation (from hardwood).

6. What fiber property affects paper softness?

Shorter hardwood fibers with thin walls and larger lumens improve softness and absorbency.

7. How do fines affect paper quality?

A controlled amount of primary fines improves bonding, while too many secondary fines reduce drainage and cause runnability issues.